There’s two sides to every coin. In the last post, I talked about instances where I usually recommend that people use an off-the-shelf tablet or smartphone device for their custom applications. The primary principle being keeping things simple, I recommend developing portable apps wherever possible, and avoiding potentially time and cost intensive hardware turns and development. But sometimes a custom (Android) tablet is required, and it’s worth knowing when to recognize these instances, and follow the path of least resistance.

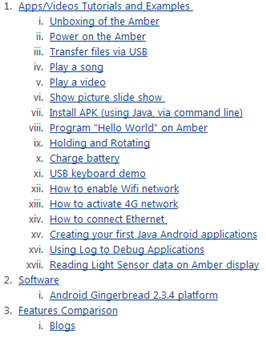

It’s why the Liquidware Amber exists. We designed it for internal use, and use in engineering projects. It saved us a ton of time having that extra level of hardware and firmware customization, without having to start from scratch each time.

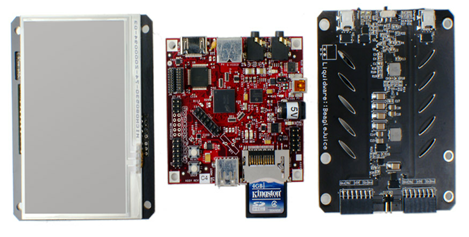

1) Sensor specificity and connection interface. In many cases, the end device is driven as much by the sensor as it is by the display. For example, a tablet may serve as the human-machine interface for a medical diagnostic device, but the sensor that is attached to it could be highly complex. Or the sensor required talks over a very specific protocol, such as I2C or SPI.

2) Custom hardware feature set. In many cases, the product calls for integrating more than just sensors to tablet HMI. Kiosks, industrial control terminals, and other large scale machinery come to mind. Nevertheless, the tablet portion doesn’t need to be built from scratch, and a custom tablet like the Amber allows for tight systems integration over several different interfaces.

3) Supply chain management with high volume. Designing a product to be deployed in volume brings other considerations into play. Considering that most consumer devices are built to be sold within a 24-month lifecycle or less, since they’re designed with obsolescence and upgrade paths in mind, the supply chain of these devices can be fickle. This means that in order to incorporate an off-the-shelf device into a product design, it’s probably a good idea to consider buying all the units you think you might need. Upfront. Which can translate to a pretty significant capital investment. A custom tablet enables tight control over the hardware manufacturing, and ensures longevity of the product, to maximize the value of upfront engineering, design, and systems integration work.

4) Custom OS and firmware. If the product is going to require highly customized kernels and special firmware that allows the tablet to integrate with other components of the device, it’s not exactly efficient to root and re-load a custom ROM/kernels on each individual unit. And voiding any sort of warranty in the process.

5) Security. The other (somewhat unexpected) driver of custom hardware requirements has actually been one of security. Understanding exactly what is going into a particular device and having control over all layers of software can help make the device less transparent and less vulnerable than stock devices currently available. For instance, a custom Android tablet include any manufacturer software, and doesn’t have GPS (if you don’t want it) so you’re not inadvertently broadcasting information that you don’t want released.

There are many other considerations, such as form factor and branding, that just might tip the scales in favor of using a custom Android tablet. And as with big questions in embedded systems development, the answers aren’t always obvious.

So if you’re on the fence about which way to take your custom tablet project, feel free to comment below, or get in touch – justin dot huynh at liquidware dot com.